This section explores how farmers and commoners of the Edo period managed time. Chimes of bell towers in castle towns and the countryside were introduced.

To Regular Life with “Hour Bells”

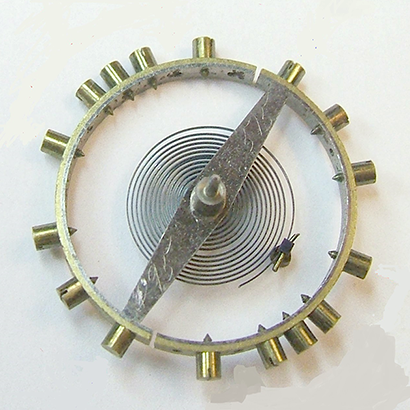

The time system in the Edo period was the seasonal time system. The seasonal time system divided a day into day and night based on dawn and dusk and further divided each into 6 periods, each of which was called an Ittoki(One Toki). Since the length of an Ittoki in the day or night varied by day and even by season, it was a very complicated time system in which an Ittoki always changed.

The main method of the time signal in those days was a bell to announce the time (“hour bell”). Some types of bells such as “Castle Bells,” “Temple Bells,” and “Town Bells” told time day and night.

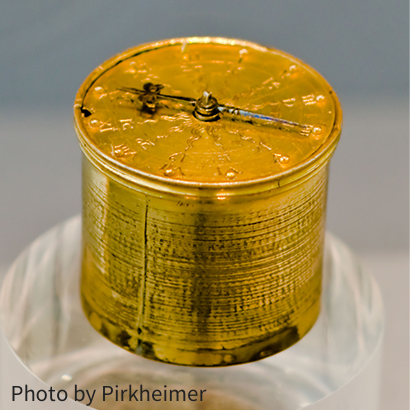

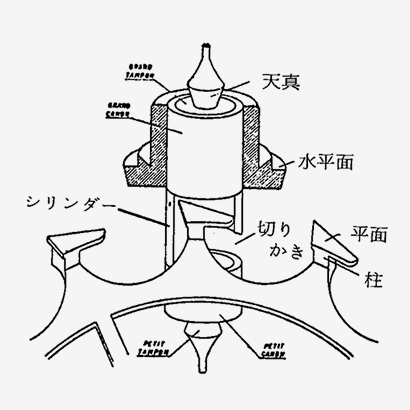

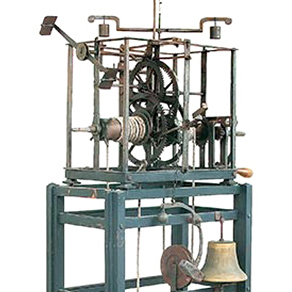

The “castle bell” informed officers who worked in the castle of official business hours at a fixed time with a drum or a bell using a Japanese traditional clock such as a lantern clock.

The “temple bell” was chimed for Buddhist and religious services in a temple using an incense clock or another Japanese traditional clock. It was originally struck three times a day (dawn, noon, dusk).

In Edo the bells were located in 9 places surrounding Edo Castle, such as in temples and towns. In rural areas outside of Edo they were installed in main castle towns such as Kyoto, Osaka, and Nagasaki. They were originally used according to the time signal system governed by the Shogunate. Later they became bells for citizens and announced the time once per Ittoki.

It was thought to be an epoch-making event when the time signal system expanded throughout all of Japan to meet the timekeeping needs of citizens in daily life.

Link between Bells in Edo Towns

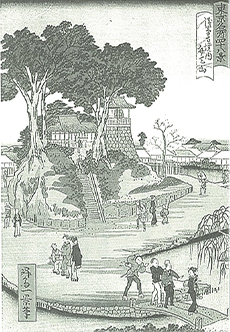

Especially in the capital in Edo town, a system to tell the common time to Samurai classes, temples, shrines, and towns became ever-more necessary as society rapidly developed. The first bell was installed in Hongokucho (current-day Nihombashi Kodenmacho). A total of 9 bells were installed around Edo Castle (①~⑨). The locations and numbers varied from time to time, but the first nine locations were ① Hongokucho, ② Ueno Kaneiji, ③ Ichigaya Hachiman, ④ Akasakatamachi Naruseji, ⑤ Shiba Zojoji, ⑥ Mejiro Fudoson, ⑦ Sensoji, ⑧ Honjo Yokobori, and ⑨ Yotsuya Tenryuji. The bells were struck in this same order, one strike after another.

Before the actual strikes, each bell in Edo was struck three times in preliminary “sutegane (pre-strikes)” to draw attention. These pre-strikes eliminated delays in the bell strikes by alerting the bell strikers at the next temples that striking time had come. Each “hour bell” in Edo seemed to have been located just within hearing range from the bell at the previous temple. The penalty was quite severe when a temple delayed striking the bell.

The bell said to be the oldest in Hongokucho may have been derived from the “castle bell” struck in Nishi-no-Maru of Edo Castle during Shogun Hidetada (1605 to 1623). This bell was transferred to Nihombashi when a bell tower was built. It was later changed to the “town bell” in Hongokucho.

Expansion of the Time Signal System throughout the Whole of Japan

In around the middle of the 17th century, the time signal system of “hour bells” linked by “pre-strikes” spread throughout the entire country. There were even claims that no places in Japan were without striking bells. This time signal system was a very innovative system in the sense that it told time by locating special facilities, deploying people, and linking bells without delay in the country. No such system was seen in Western countries, even by the end of the 19th century, an age of modern railways and telegraphy. The time system suggests that the people of the day had acquired the punctual Japanese character now exemplified by modern-day train schedules.

Hour bells were struck by specific persons such as “contractors” and “bell strikers,” or by each temple or shrine. The cost was covered by imposing bell striking fees or religious mendicancy.

What was Time Sense of Commoners in the Edo Period like?

The “hour bell” seemed to be an essential part of daily life as a bell ticking out the rhythm of the commoners’ days in Edo. Some Senryus and haikus from the Edo Period show the central role of the “hour bell” in the lives of the period.

・Basho Matsuo

”Cloud of flowers, is the bell struck in Ueno or Asakusa?”

・Bell in Hongokucho (Kokucho)

・”Kokucho makes Edo sleep and wake” (Commoners in Edo lived based on the “hour bells”)

・”Left Edo Nihombashi at the 7th Toki” (Left Edo at 4 a.m. in the dark)

The bell in Kokucho is called the “Excluding Bell from Ueno.” The temple gate of Ueno seemed to be opened and closed based on the strikes of the bell in Kokucho.

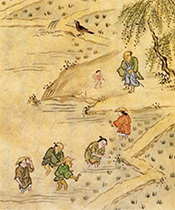

How did the Farmers and Merchants of Rural Areas Experience Time?

How did the farmers in local cities far from Edo experience time?

A diary in which a farmer recorded time around the middle of 18th century was found in materials of “History of Wakayama.” Not only warriors and great landowners, but also ordinary farmers systematically worked based on a fixed time. They arranged an order and time with neighboring villages to irrigate their irrigation channels and carried out agricultural work in an orderly fashion while keeping time. In this way, time of the whole community strongly governed production and people’s lives in the agricultural society.

How, meanwhile, did merchants experience time?

Sayings related to time -“the early bird catches the worm”, “Late riser is the poor cause,” “work diligently valuing even a second,” etc.- were adopted as mottos to impose basic standards of conduct for merchant families. Some merchants forced their employees to follow strict curfews, like “Open the shop at 6 a.m. and close at 10 p.m.” For merchants, having their employees keep time was an important rule and precondition for a diligent workday.

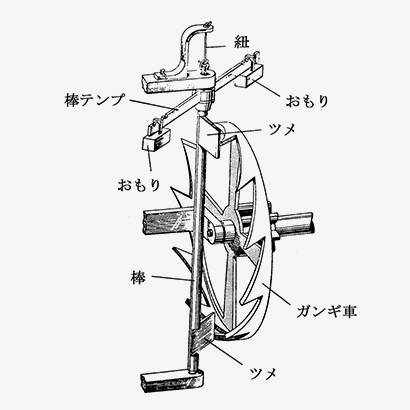

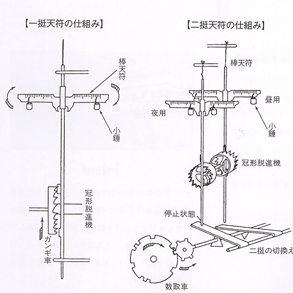

Small bells mounted on the skewers of incense clocks located in tower bells announced the time to the strikers of the larger hour bells. When the skewers had burned, the small bells were struck without delay.

People in Osaka soon learned from Edo and began their own custom of striking town bells. The town bells were essential to foster the basic behavioral discipline of merchants in Osaka, “who respected early rising and punctuality.”

Time Governed by Communities

Time in Japan had basically been on a community basis through the Edo Period and mainly managed by landlord classes who had governed the communities. Time is to make the community work in a systematic, orderly fashion in a group. Western concepts and values such as “time is money” were not widely adopted. The sense of time experienced as an individual independent from the community was established after the Meiji Period in Japan.

Decline of “Hour Bells”

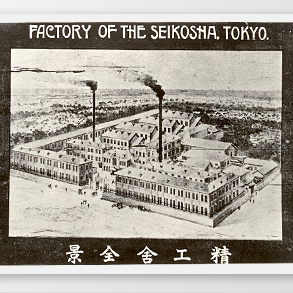

The time signals according to the seasonal time system gradually disappeared after the “temple bells” were removed from shrines to comply with the Law to Separate Buddhism and Shintoism in 1868 and the solar calendar and the fixed time system were introduced in 1873 under the calendar reform in Meiji Period. The time signal system governed by the “hour bell” declined due to the expansion of tower clocks constructed under the fixed time system in various areas in the late Meiji Period.

References

・Tsunoyama, Sakae, Social History of the Timepieces. Chuko Shinsho

・Urai, Sachiko, Time in Edo and Hour Bells, Iwata Shoin

・Yoshimura, Hiroshi, Bells in Great Edo Period Onpoki. Shunjusha

・Kashiwagi Family’s Document. Taito Library