1. Introduction

The significant advances of clock technology in the West world date back to the Age of Discovery in the 15th century and later, when nations pursued for the dignity and with high prize money the development of the “marine chronometer,” an extremely accurate clock essential for safe ship navigation. The steam engine invented during the Industrial Revolution of the mid-18th century established the railroad industry, which promoted the development of the small and accurate “railroad watch” for safe railroad operation.

In those days, Japan had no chance to catch up with the global standard of clock technology. Japan was first engrossed by war within the country and then shut off from the rest of the world by a national isolation policy banning outward voyages. The Wadokei (traditional Japanese clocks) Japan produced for its seasonal time system were highly regarded for both their decoration and technical intricacy, but they fell far behind modern technologies in precision, in miniaturization, and in many other ways.

2. Japan-made Clock Industry in the Early Meiji Period

In 1872, Japan switched from its seasonal time system to a fixed time system in conjunction with a calendar reform (from the old lunisolar calendar to the new solar calendar). This brought Japan’s clock industry to a significant turning point. Japan’s traditional clocks for the seasonal time system, apparatuses that had been produced for nearly 300 years, became useless. Japan had no choice but to rely on imported items to satisfy the large demand for clocks after the country opened its doors.

The Japan-made timepiece industry emerged in around 1877 when a small number of manufacturers in Tokyo, Nagoya, and Osaka began small-scale production based on wall clocks and pocket watches from the West.

3. Establishment of K. Hattori & Co.

Kintaro Hattori established K. Hattori & Co. (the present Seiko Holdings Corporation) in 1881 to sell and repair imported clocks and watches.

4. Establishment of Seikosha Factory and Production of Wall Clocks

n 1892, 11 years after the establishment of K. Hattori & Co., Kintaro founded Seikosha Factory in the area of the present Sumida Ward, Tokyo to produce wall clocks. The Factory began with wall clocks for two reasons: they were more easily produced than pocket watches and a competitor in Japan had already demonstrated the cost-effectiveness of Japan-made wall clocks compared to imports.

The production method at Seikosha Factory integrated almost all processes in-house (vertically integrated production). In addition to processing and assembling the mechanical parts, the factory produced most of the dials, hands, wooden cases, and other exterior parts. The production of some parts was converted from outsourcing to exclusive affiliated factories.

Compared with horizontally divided production, the method adopted by other Japanese wall clock manufacturers, vertically integrated production produced items of much better quality and enabled product development at greater speeds. In six to seven years, Seikosha Factory was the largest producer of wall clocks in Japan.

5. Pocket Watch "Time Keeper" and Alarm Clock

Seikosha Clock Factory introduced pocket watches in 1895, three years after its founding, and then alarm clocks in 1899. Japan-made clocks and watches were now strongly positioned in a market dominated by imported timepieces.

The company’s alarm clocks with nickel-plated rust-proof cases became a special favorite and soon dominated the Japanese and Chinese (Shanghai) markets, taking the market away from popular alarm clocks from Germany (iron cases).

This is how Seiko Clock Factory became Japan’s only general timepiece factory producing three categories of product – wall clocks, table clocks, and pocket watches – within only a decade from its founding.

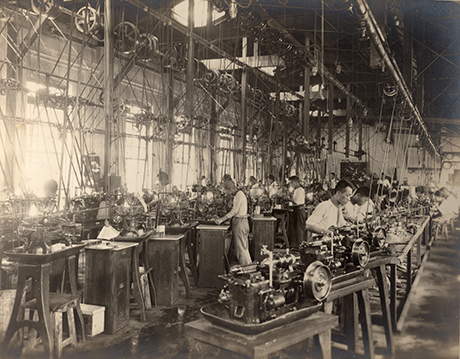

6. Innovative and State-of-the-art Production Equipment

In 1899, Kintaro Hattori took his first journey to the West to study timepiece factories and purchase new steam engines and large troves of the most advanced machine tools. Upon his return he refurbished the Seikosha Factory and commenced mass production for the first time.

The outbreak of the Russo-Japanese war in 1904 mandated Seikosha Factory to engage in the production of fuses for shells and other military items. The transfer of military know-how for machining promoted the technical advancement of Seikosha Factory and the development of methods for mass production.

Four years later, in 1908, the self-developed “automatic pinion lathe” dramatically raised the productivity of the pinions, a bottleneck in pocket watch production.

7. Popular Pocket Watch "Empire"

The Empire, the popular pocket watch introduced in 1909, became a smash hit thanks to the factory’s automatic pinion lathe, a technology that enabled mass production. The Japanese market was dominated by two products, Swiss-made pocket watches and the Empire. K. Hattori & Co. decided to begin the full-fledged export of its Japan-made masterpieces to China. The Empire was to stay in hot demand for all of the 26 years it was produced, a period spanning through the Meiji, Taisho, and early Showa periods, all the way up to 1934.

In 1911, the 19th year from its founding, Seikosha Factory commanded a 60% share of production in Japan and became a dominant player in Japanese timepiece industry.

8. Introducing Japan's First Wristwatch, the Laurel

In 1913, Kintaro Hattori introduced Japan’s first wristwatch, the Laurel. The commercialization of the Laurel in 1913 must have been an extreme challenge, considering that producing wristwatches in the world had started in around 1910. Downsizing to the “12 ligne” size (φ26.65mm) was tremendously difficult given the technological level and production equipment available in those days. The work to downsize accelerated the advancement of design and microfabrication techniques and the development of machine tools.

The outbreak of World War I a year later in 1914 generated a new demand for wristwatches all around the world. By great coincidence, the Laurel was commercialized on a perfect occasion.

9. The Great Kanto Earthquake and Birth of the Seiko Brand

K. Hattori encountered its greatest crisis ever. The Great Kanto Earthquake of September 1923 burnt down the factories and offices of K. Hattori & Co., forcing the company to suspend production and sales. Through sheer fortitude, K. Hattori opened up for business only a month later and Seikosha Factory resumed production in March of the following year.

From 1928 to 1933, Seikosha Factory constructed a succession of modern production plants, refurbishing production lines with state-of-the-art machines. The growth over those five years firmed the foundations for K. Hattori’s subsequent progress in the production of clocks and watches.

In 1924, the first post-earthquake year, a new brand called Seiko was born. By launching Seiko, Kintaro Hattori hoped to go back to the founding spirit to 'produce Seiko = precise timepieces'

The Seikosha pocket watch was certified as Japan’s official railroad watch in 1929. Japan’s railroad company launched in 1872 had long used railroad watches from the West. By choosing Seikosha as the most accurate and reliable railroad watch available, the railroad gave Seiko confidence. At last Kintaro Hattori’s company was catching up with its Western competitors in the timepiece industry.

Stagnation and contraction during World War II

In 1937, Seikosha Factory divided its watch section to establish Daini Seikosha (in Kameido, Tokyo), a new firm dedicated to the enhanced production of watches.

World events interfered. The consecutive outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937, World War II in 1939, and the Pacific War in 1941 forced both Seikosha Factory and Daini Seikosha to shift to full-fledged production for the war effort. The production of watches and clocks for civilians was reduced year by year and virtually suspended by the end of war in 1945.

Daini Seikosha (Kameido factory) was devastated by war damage. Production had to be restarted in evacuation factories located in Kiryu (in Gunma prefecture), Toyama, Sendai, and Suwa (in Nagano prefecture). At the end of 1949, all these evacuation factories but Suwa were shut down to redirect resources to the restoration of the Kameido factory (the Suwa factory later became Suwa Seikosha, the present-day SEIKO EPSON CORPORATION).

While production got on the right track to some extent, the company still suffered a number of quality-related problems resulting from the aging of machinery, inferior materials, and technological stagnation during and after the wars.

After the war the Japanese government promoted the “recovery of civilian productivity” as a top priority goal and adopted a policy of building Japan into an export-oriented nation. The timepiece industry, one of Japan’s light industries, was ranked assigned top priority and given continuous support from academia and the government to improve quality. These social and political shifts supported the reconstruction of Seiko. In 1948, the former Ministry of International Trade and Industry started the Council for Quality Inspection of the Japan-made Watch and Clock (timepiece competition). The new council was a strong force behind the further advances in quality in Japan’s clock and watch industry.