Birth of Breguet, the genius watchmaker

Abraham-Louis Breguet was a watchmaker born in Neuchâtel, Switzerland in 1747. Breguet’s perpetual calendar, and Tourbillon, and other groundbreaking inventions advanced the history of the watch by 200 years. His peers called him the “Leonardo da Vinci of the watchmaking world.”

Breguet was born the first son of Jonas-Louis Breguet, the descendant of a prominent family who had lived in the Neuchâtel region since before the Protestant Reformation. Breguet’s mother married a watchmaker after her husband’s death in Breguet’s eleventh year. At the age of 14 he quit school to apprentice to a local watchmaker in Les Verrières, with plans to become a master watchmaker. A year later he moved to Versailles in France to refine his watchmaking techniques. There he acquired knowledge of physics, optics, astronomy and mechanical engineering from the learned Father Marie, a clergyman with whom he kept close in touch. The knowledge he collected in France contributed to his inspired and prolific watchmaking activities for the rest of life.

Establishment and Success of the Breguet Brand

In 1775, at the age of 28, Breguet established the "Breguet" watch brand out of a new studio in Quai de l'Horloge on Cité Island in the Seine River in Paris. In the same year he married Cécile Marie L'Huillier, the daughter of a bourgeois family. Their first child, Antoine Louis, was born the next year. Breguet's domestic happiness soon proved to be ephemeral. In the next few years his second and third children died of illness, and in 1780 his wife Cécile passed away at the young age of 28. Breguet suffered from deep sadness and was never to marry again. Yet just when his family was dying, Breguet invented the "Perpétuelle," a watch he had worked on through long years of study. The Perpétuelle was the first step of what was to become a glorious career in watchmaking.

In ensuing decades he invented a succession of watches that were innovative both technologically and aesthetically. Breguet watches won the praise of many royals and nobles, the elites of Europe, including King Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette. Breguet was fully conversant with the latest advances in science outside of his craft of advanced watchmaking. His curiosity and expansive knowledge helped him become one of the greatest inventors in the history of watches. Many of his wide-ranging innovations live on in the mechanisms of the mechanical watches being produced today. Let’s explore some of Breguet’s legacies.

Breguet Legacies Still Alive Today

1780, Perpétuelle (Automatic Winding Watch, aka the "Automatic")

Breguet designed the world’s first reliable automatic winding watch. As the person wearing the pocket watch walked or rode in a vehicle, a weight attached to the movement vibrated in an up-and-down motion that automatically wound the mainspring. As long as the person kept in the habit of moving, the mainspring stayed wound and the watch told time perpetually. The first Perpétuelle was sold to the Duke of Orléans in 1780. The timepiece was doubly unique for its "power reserve indicator," a tiny meter on the dial plate that showed the level to which the mainspring was wound, and the small second.

※This page uses the French term "perpétuelle" in place of "perpetual." Brueget called the watch a "montre perpétuelle (perpetual watch in French)" when he first developed the automatic winding mechanism.

1783, Gong for a Repeater Watch

The "minute repeater" was a mechanism that told time known on demand in the darkness of night, in either 15 minute or 1 minute steps. In 1783 Breguet invented the innovative method by placing a steel wire gong along the outer periphery of the movement in place of the À toc, a hammer that struck the case directly in the repeater. The new gong system helped watchmaker’s design thinner watches that produced cleaner sounds. Most watchmakers of the time adopted Breguet’s minute repeater mechanism.

1783, Breguet Hands and Breguet Numerals

Breguet 's creative flare is conspicuous in his various aesthetic designs as well as his intricate mechanisms.

Breguet Hands and Breguet Numerals

In 1783 Breguet designed his uniquely shaped "Breguet hands" with their sharp points, hollowed out circle motifs, and beautiful blue (the color of heat-treated steel). He also developed "Breguet Numerals," Arabic numerals of a distinctive typeface that lean slightly to the right and are often placed over white enamel dial plates. Breguet Hands and Breguet Numerals are still common parlance in watchmaking language.

Guilloche Pattern

The "Guilloche" is a decorative technique in which a very precise and repetitive pattern is engraved into an underlying material (in watchmaking, a dial plate) using a manual lathe. The Guilloche has been widely used since circa 1786 as a favorite design technique of Breguet. More than merely decorative, a Guilloche pattern suppresses the reflection of light on metal dial plates. It still appears on many timepieces of today.

1790, Pare-Chute System (Shock Absorbing System)

When a watch is dropped or incurs a strong impact from the outside, the pivot of the balance wheel, in the movement, is fatally damaged. In 1790 Breguet invented a system to prevent this damage by absorbing the shock applied to the balance. He called the system the "pare-chute." The tip of the pivot of the balance wheel is cut into a cone shape, fixed in place with a dish of a matching shape, and mounted on the strip with a spring. The pare-chute is the forerunner of the modern “Incabloc” system.

Breguet employed the pare-chute in all of the Perpétuelle watches produced after 1792, and in every other model to come later.

1795, Perpetual Calendar

In 1795 Breguet developed a perpetual calendar system that showed the day of the month, the day of the week, and the name of the month while automatically correcting the calendar using a special cam to adjust for the leap year cycle. Breguet lived in Switzerland during this period, insulated from the turmoil of the French Revolution.

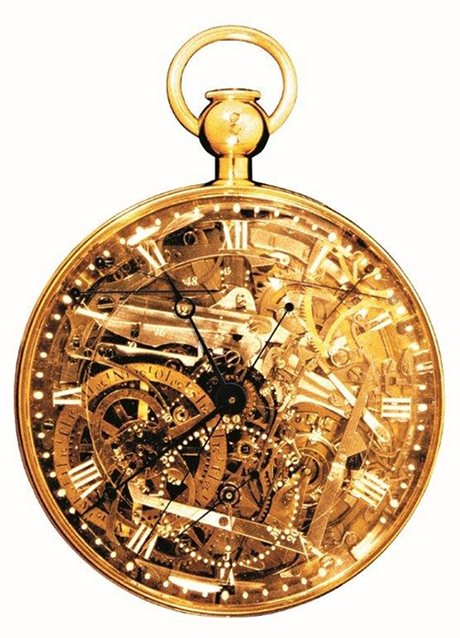

1801, Tourbillon

In 1801 Breguet patented the "Tourbillon" ("whirlwind" in French) escapement, one of the finest expressions of the watchmaking art.

Watches usually gain or lose time under the force of gravity when they change the position following the move of the wearer. The "Tourbillon" mechanism reduces the impact of gravity to the greatest possible extent. It is structured as a speed-governing escapement (balance and escapement) that creates a precise rhythm and rotates the wheel at a constant speed in a case called the "cage (carriage)." The wheel rotates the cage enclosing it, which reduces the error in advances and delays caused by the change of position.

1810, Queen of Naples

Breguet reportedly made the first wristwatch ever known at the request of Carolina Murat, the sister of the Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte. Breguet named the watch the “Queen of Naples” in deference to Carolina, who herself held that position by marriage at the time. The movement with the repeater function was said to have been installed in a slim case and mounted on a wristlet of hair and gold thread.

1815, Marine Chronometer

In 1815 Breguet designed a high-precision marine chronometer with two barrels. He was bestowed the title of "Horloger de la Marine" (the watchmaker to France's Royal Navy) in the same year. For watchmakers of the 18th and 19th centuries, it was the highest honor to be engaged as a manufacturer of the "marine chronometers" used to determine the longitudes of ships at sea.

1820, Split Second Chronograph

The split second chronograph is engineered with two second hands for measurement. Both hands overlap and start simultaneously, but one can be stopped independently in the middle of measurement and instantly fast-forwarded to catch up with the other afterwards. This function allows the measurement of the intermediate times (split times) or elapsed times of two different events in motion. The modern split second chronograph is based on this invention.

1827, "Marie Antoinette," the Ultra-Complication Watch

On commission from the French Queen Marie Antoinette in 1783, Breguet began developing an ultra-complicated timepiece he called his "Marie Antoinette." The commission required that the watch perform every function Breguet had developed to date. The project called for extremely delicate techniques. The work was succeeded by Breguet's disciples after his death, and was finally finished in 1827, 44 years after the commission and 34 years after the death of the queen herself. The Marie Antoinette displayed the "equation of time," the actual difference between the mean solar time and the true solar time based on the actual movement of celestial bodies.

Reputation as the Great Watchmaker

As recounted above, Breguet invented many unique watchmaking techniques and designs that live on today. He was said to have been bound to important persons in every grade of society by feelings of respect and a philanthropic spirit. Beyond his exquisite talents as an engineer, he had an affable disposition marked by humility, sincerity, and good cheer. Breguet invited excellent watchmakers from all over Europe to apprentice with him and generously shared his techniques, his knowhow, and the directions of his study. He also established a distinguished lineage and eminent watch manufacturing company that has commanded a premier reputation in the watchmaking world since its founding in 1775.

References

Breguet, Emanual "Breguet, Horloger Depuis 1775"