The Spread of Christianity and Timepieces

Beleaguered by the ceaseless tumult of their times, many medieval Christians of the west prayed for the promulgation of the Savior and Christianity. Church bells were struck three times a day (morning, noon, and evening) or every three hours in churches and convents throughout all of Europe.

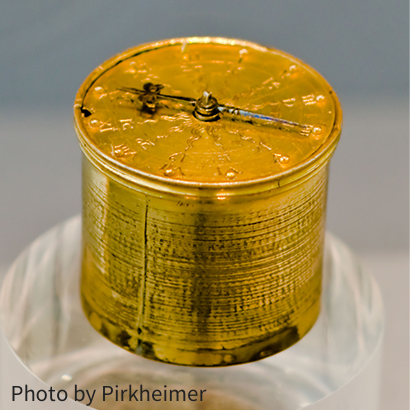

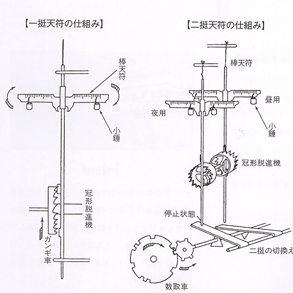

The daily routines for prayer, work, and reading in the convent were strictly governed by time. Nuns, monks, and priests followed rigorous precepts and codes of behavior for all of their religious activities and events. Manual clocks of many types were used to record the times of announcements and directives. Common types included clepsydras, sundials, sandglasses and candle clocks with markings calibrated in minutes or hours. Timekeepers closely watched the clocks and rang bells to broadcast the time every 15 or 30 minutes. They awaited a clock capable of ringing a bell automatically.

Emergence of the First Mechanical Tower Clock

The world’s first mechanical clock capable of automatically striking a bell was said to have been installed in the tower of a convent and church in the Renaissance, in around 1300.

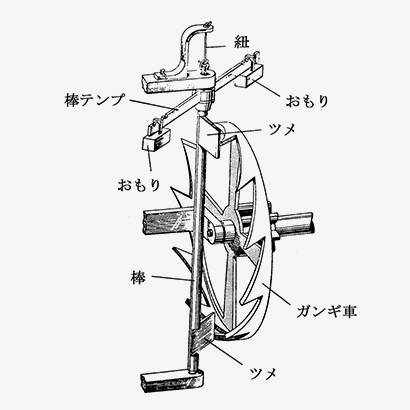

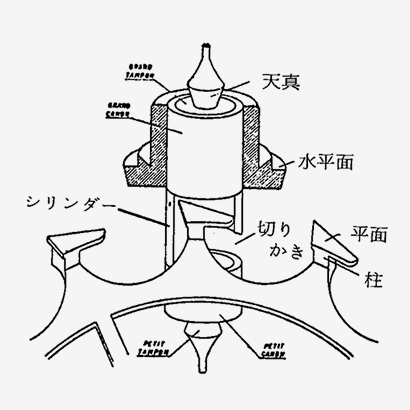

Driven by the force of weights, the clock and bell were installed high in the tower to maximize the distance the weights would drop. The crown wheel escapement was fashioned on the wheel of the weight to fix the speed of the wheel’s rotation and regulate the drop of the weight rather than letting it fall all at once.

The most important role of the clock was to tell time for the monks, who organized their religious activities according to a time-governed schedule. Not long after the clock was installed, the time kept at the convent was adopted as the public time for people living nearby. Eventually it became the time for the whole society, conveniently sounded by the resounding bell in the tower.

By the way, the word “Clock” derives from Clocca, the Latin word for “bell.”

From a Seasonal Time System to a Fixed Time System

The mechanical tower clock, which sounded one chime for every hour -once at 1 o’clock, twice at 2 o’clock, and so on- was said to have spread from Italy across the Alps to Germany, France, and England in the 14th century. The adoption was encouraged by the Christian Church and later churches and convents all over Europe. When cities began to install mechanical tower clocks in public squares such as city halls and markets in the 15th and the 16th century, citizens began to order their lives according to the fixed time system.

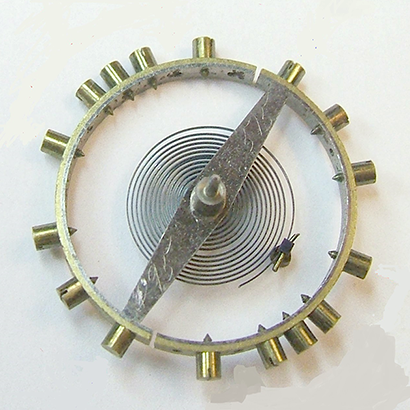

When the precision of mechanical clocks improved in the late 16th century, clocks were installed in all cities, inculcating a consciousness of fixed time all over urban Europe.

People in the countryside continued to live by diurnal and seasonal rhythms. People in the cities lived by fixed time, by the ticking of the mechanical clock.

Revolution in Our Consciousness of Time

Since time was originally governed by God according to the Christian faith, the Church censured acts to gain profits (interest) by selling time as blasphemies against God. But when life based on fixed time came with the advent of the mechanical clock, merchants and craftsmen in cities gained from the concept of working hours in their commercial and industrial ventures. Conflicting views of time created friction between the Church and commercial classes.

The change in the consciousness of time revolutionized society. Time became an objective phenomenon apart from God in the community. The pursuit of profits using time systematically based on fixed time was justified, as the value of a product was measured by the human capacity and time spent to produce it.

In this way, the mechanical clock became a means of social and political control for the merchants governing free cities. Time came to be measured as precisely as money itself, shifting society closer to modern capitalism.

The Formation of Early Capitalism

“The Statute of Apprentices,” a directive specifying an hourly wage for workers in the country, was already established in England in 1563, during the reign of Elizabeth I.

Time shifted from a community-owned resource to a private asset, though only the rich-royalty, titled nobility, and the bourgeoisie could actually afford to purchase the extravagantly priced clocks of the day. This was a great advantage for the bourgeoisie who could buy clocks. They helped to form the first iterations of modern capitalism by equating time with wages, starting in about the late 16th century.

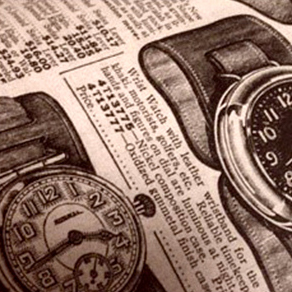

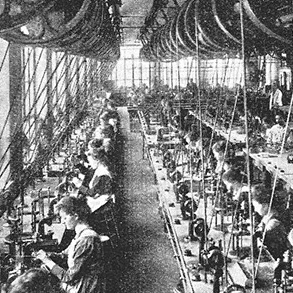

The mass production of the watch started when the pocket watch became affordable by middle class families as well as the rich bourgeois, in the late 18th century. Until then, the bourgeoisie had forced workers to work long hours. The workers were cheated of their time.

Capitalism is a social system in which the capitalist, the owner of the means of production, profits from the labor of wage earners, who hold no stake in the capitalist’s enterprise. Time management with the timepiece played an important role in the system.

References

・Hirai, Sumio, The Story of Timepieces. The Asahi Shimbun

・Tsunoyama, Sakae, Social History of the Timepiece. Chuko Shinsho

・Yamaguchi, Ryuji, Timepieces. Iwanami Shinsho

・Ueno, Masuo, The Story of Timepieces. Hayakawa Shobo