Britain was behind in Germany and France

The British started to construct tower clocks in churches in the 14th century, but the clocks were actually built by clockmakers called in from Holland. Later, after the 16th century, the pocket watches, room clocks, emerging from Britain seemed to be the works of German clockmakers and German techniques.

Britain was behind Germany and France in the timepiece industry. The British still produced weight-driven wall clocks with Foliot balances and lantern clocks placed in special brackets even in the mid-16th century, when spring-driven clocks started to supersede them on the Continent.

Lantern clocks were later driven by spirals with pendulum regulators. The British continued using them until as late as the mid-18th century.

Many clockmakers exiled by the French Wars of Religion immigrated to Britain in the late 16th century. The British clockmakers had much to learn from their continental counterparts, but snubbed them out of fear that they would outcompete them in business. Their refusal to warm to their rivals held the British timepiece industry back for many more years. The British lagged behind until a surge of innovation came in the mid 17th century.

The timepiece industry in Germany and France had prospered with the support of the Protestants. Then, through the hardships of persecution and exile, it started to decline in the early 17th century.

Appearance of Excellent Clockmakers from the Late 17th Century

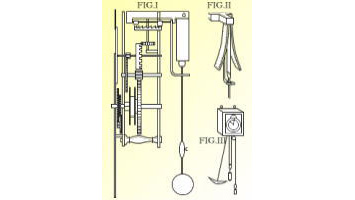

Ahasuerus Fromanteel, a Briton of Dutch descent, made a longcase clock using a long pendulum by applying the pendulum clock patented by the Dutch inventor Christiaan Huygens in 1657. This was the very first British Traditional Grandfather’s clock, a valuable piece of furniture that stood taller than a man. Grandfather clocks boomed until the mid-19th century.

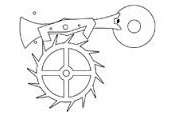

Clockmakers in London thought of further improving this pendulum clock. Robert Hooke and William Clement invented, and later improved, the recoil escapement, replacing the crown wheel escapement to increase precision by reducing the amplitude. Thomas Tompion, George Graham, and Thomas Modge, clockmakers from three generations linked by master-apprentice ties, focused their efforts on the development of a more highly evolved escapement for clocks and pocket watches from the late 17th century to late 18th century.

Methods were also contrived to reduce wear and damage by mounting a jewel in the pivot of anchor striker.

Eventually, in 1756, Modge invented a small, precise lever escapement that could be easily mass produced, a precursor of the club-tooth lever escapement used in today’s watches. With this invention, the British timepiece industry became a key driver of the Industrial Revolution.

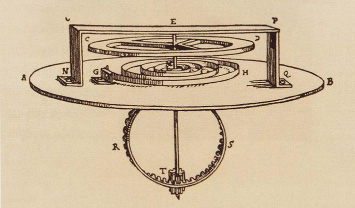

Tompion, who Laid the Foundations for Production in the Timepiece Industry

An apprentice of the day typically learned the techniques to produce a complete timepiece during a seven-year apprenticeship under a master of the guild. Tompion branched out by introducing a production method called “Manufacture d’horlogerie.” The work to produce a timepiece was divided into separate stages at Tompion’s workplace. The result was the reliable production of inexpensive, quality timepieces through cooperation. A rotary cutter Tompion developed with help from his friend, the genius inventor Robert Hooke, could cut many different parts with high accuracy. The invention was key to the manufacturing process.

Tompion is remembered as the father of English clock-making. The standardized American system of manufacturing and the foundations of the manufacture and assembly of interchangeable parts in the 19th century started from him.

Timepiece Technology, a Key Driver of the Prosperity the Industrial Revolution Brought Britain

Looking at British society at that time, we can see the importance of Britain’s victory in the Seven Years’ War between the European powers of 1763. The victory was key to the country’s hegemony over markets and resources in the Americas, India, and elsewhere. The interests it gained from its colonies were stable and vast. Within Britain, the improved agricultural technologies of the so-called Agricultural Revolution unleashed a deluge of migration from the countryside into workplaces in the cities. Cheap labor for industrial production was abundant.

The industrial revolution evolved in stages, powered by human capital. First came the timepiece industry, a bastion of advanced technology. Next came the textile industry, with the latest spinning machinery. Then came the steel industry, with improved steelmaking technology. The invention of the steam engine by Watt in 1785 created a highly demanded source of power for factories, steamships, and steam locomotives, driving the revolutionary development of the machine industry by the middle 19th century. Timepiece engineers, who had mastered physics and mechanical engineering, were the best engineers of their day. The spinning machine and steam engine were both said to have been invented with escapements that converted rotary motion into shuttle motion, as set out by the cam theory. The application of these machines using escapement technology from the timepiece industry played a great part in the sudden rise of the Industrial Revolution.

Emergence of the Mass Consumption Society

Timepieces were once luxury items only purchased by landlords, the nobility, and bourgeoisie merchants. According to statistics from the late 18th century, Britain produced 120,000 to 190,000 pocket watches in a typical year. Continental Europe produced 100,000 to 150,000, and America produced zero. Britain produced more pocket watches than any other country and sold more of its watches to its own public. Unlike today’s British, who are commonly regarded a traditional and conservative in lifestyle and dress, the Brits of the 18th century regarded pattern-dyed cotton from India, exotic black tea from China, and pocket watches as luxuries affordable to only the rich and noble. Men and women of the middle and working classes widely purchased pocket watches as once-in-a-lifetime luxury items in a period when pocket watches were only used by the privileged classes on the Continent.

References

・Hirai, Sumio, The story of timepieces. The Asahi Shimbun

・Tsunoyama, Sakae, Social History of the Timepiece. Chuko Shinsho

・Yamaguchi, Ryuji, Timepieces. Iwanami Shinsho

・Ueno, Masuo, The story of timepieces, Hayakawa Shobo