Clockmakers appeared everywhere in Japan after the calendar reform of the early Meiji period. Let’s see how the timepiece industry continued to gradually develop during and after the Meiji Period.

Satsuma and Choshu Armies: Western Watches Already Used in Battle

After Yokohama Harbor was opened and foreign concessions were approved in 1859, James Favre-Brandt, a secretary of a Swiss envoy visiting Japan, was summoned to serve an unofficial advisor for the Satsuma Domain and procurer of firearms such as guns and ammunition. He had already opened a foreign trading house in Yokohama, in 1864, as his father was a traditional jewelry designer for timepieces in Le Locle and he had started importing Swiss wall clocks and pocket watches in Japan 8 years before the calendar reform as part of a plan to spread both timepieces and Western weaponry to Japan.

Having learned from military defeats by the UK and European Combined Fleet, the Satsuma and Choshu Armies mapped out a detailed time management strategy based on the fixed time system in its campaigns in the Boshin War against the Shogunate (1868-69). Western firearms and pocket watches purchased from Favre-Brandt gained them a keen advantage over the Shogunate forces, who fought with old-fashioned weapons according to rough strategies based on the seasonal time system using traditional Japanese clocks.

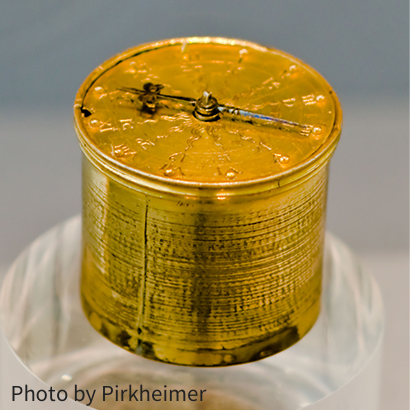

The defeat of the Shogunate’s traditional army by the carefully controlled strategy and modern weaponry of the Satsuma and Choshu Armies is unsurprising. Reports hold that a gold-cased pocket watch manufactured by Longines in 1869 was left behind in the estate of the legendary samurai Takamori Saigo.

Confusion by the Calendar Reform of the Meiji Period

After the Meiji Restoration in 1872, the Meiji government supplanted various existing systems with a program of new reforms, including a calendar reform, under a so-called ‘civilization’ policy. The government adopted the solar calendar in place of the lunisolar calendar and introduced a fixed time system based on detailed divisions of the hour, minute, and second.

Yukichi Fukuzawa, who had experienced the excellence of the Western culture and convenience of the new calendar on visits to Europe and America, issued the “Kairekiben (An Explanation of the New Calendar)” to enlighten the public on the advantages of the Western system.

His book went so far as to say,“ Those who doubt the new calendar must be fools lacking in both intelligence and literacy. Those who don’t doubt must be wise and acquire knowledge through study at once.”

The calendar reform helped to limit confusion in the trade and diplomatic dealings of the Western powers and popularize gold-cased pocket watches as a status symbol among the wealthy and government officials. Wall and table clocks were installed in public institutions such as schools, governmental offices, police and postal stations, and stores.

It took years, however, for the general public to accustom themselves to the new calendar system. The change from the lunisolar system, with a leap month coming every three years, to the solar system, with a leap day coming every four years, required the rescheduling of annual farming events, festivals, and the like. The new and different schedules for events such as O-Bon caused considerable confusion in daily life.

The Fixed Time System and Rise of the Timepiece in Commerce and Industry

The fixed time system eventually took root throughout all of Japan when a timetable was established for national school education from the 1880s. The demand for timepieces was further strengthened by growth in the nation’s student and white-collar populations and the emergence of a middle class in urban areas due to improvements in advanced education and growing numbers of established companies.

More and more timepiece retailers opened in urban centers such as Tokyo, Kyoto, Nagoya, Osaka as the timepiece became part of daily life. Some shops also opened their own timepiece factories.

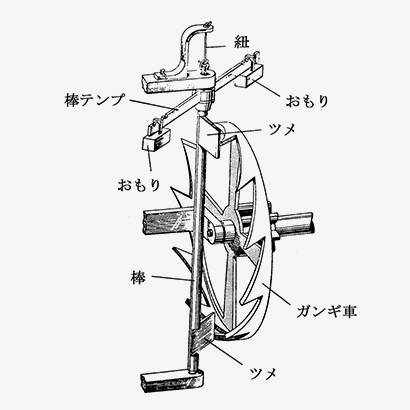

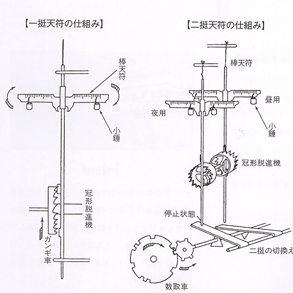

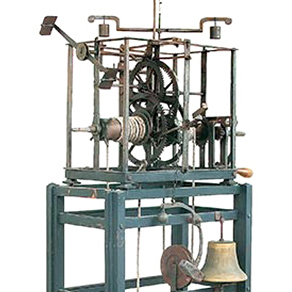

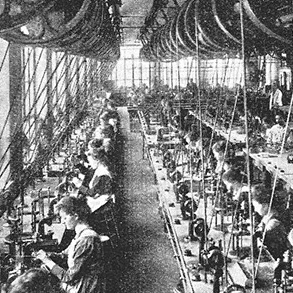

Clockmakers in the early Meiji period spent most of their time altering traditional Japanese timepieces based on the seasonal time system to the fixed time system or repairing Western clocks installed in foreign trading companies. When demand increased after the middle Meiji period, clockmakers all over Japan built wall clock factories based on manufacturing technologies copied from Europe and America. Commerce and industry of timepieces in Japan prospered.

Timepieces at the time were expensive but easily went wrong. Purchased timepieces were expected to serve for the rest of their owner’s lives, but not without periodic repairs. Clockmakers learned additional skills as experienced repairmen. Many built manufacturing factories for wall clocks in the four urban areas where clockmakers gathered.

The Timepiece Industry Developed in Nagoya and Osaka

Jiseisha (Hayashi Clock), the first Japanese factory for wall clocks, was established in 1887 in Nagoya, a home territory for the Tokugawa Shogunate where the clock-making tradition had been passed down from the era of the Japanese traditional clock. Nagoya later became a timepiece production base for ten-some manufacturers of finished products and a host of related factories for parts and cases.

In Osaka, Osaka Timepiece Manufacturing Co., Ltd was established in 1889, introduced technology and manufacturing facilities from America in 1895 and succeeded in producing Japan’s first domestic-made pocket watches.

Seikosha’s Differentiation Strategy

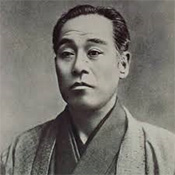

Kintaro Hattori, the founder of Seiko, was born in 1860. He apprenticed in a clock shop at the age of 13 and established K. Hattori & Co., a small enterprise specialized in the repair and sales of timepieces, in 1881. He built Seikosha, his factory, at the age of 31 in 1892.

Before founding Seikosha, Kintaro is believed to have visited Jiseisha in Nagoya to study the manufacturing of wall clocks together with the chief engineer Tsuruhiko Yoshikawa.

The other manufacturers of wall clocks, most based in Nagoya, went bankrupt within a few years from the founding of Seikosha. Most had been joint-stock companies enmeshed in price competition in a market for lower quality products. Their funds ran short when they failed to pay investors high dividends.

Seikosha focused on manufacturing expensive but high-quality timepieces to avoid the price competition and grew sales by producing differentiated products such as metal-cased table clocks, Japan’s first alarm clock, and several other unique models such as a one-of-a-kind crystal-faceted clock from Edo for mantel design.

Kintaro Hattori Acquires Western Technology

Two visits to timepiece factories in Europe and America in 1899 and 1906 helped Kintaro dramatically improve Seikosha’s manufacturing technologies, expand its sales, and enhance its organization.

In his visits to the Waltham and Elgin factories in America, Kintaro learned rational layouts for standardized mass production lines for the components of wall clocks and pocket watches, as well automated manufacturing management systems for parts. In Germany, France, and Switzerland he had the opportunity to study unique small-lot production systems for various table clocks and pocket watches with unique designs. He also visited timepiece schools and dormitory systems set up in European factories.

Impressed by the mass production system in America, he started to employ young workers and built a dormitory in his factory. Teachers invited from nearby private schools came to the factory at night to tutor his workers on subjects such as Japanese and mathematics.

In spite of the competition Kintaro posed as a foreign manufacturer, his personality and natural virtue are thought to have won over the major timepiece manufacturers in Europe and America. Kintaro was welcomed into their factories.

Resurgence of the Pocket Watch with an Automatic Lathe Developed In-house

In 1908, Seikosha built an innovative automatic pinion lathe capable of completing the three processes of rough machining, gear cutting, and final finishing all at once. Tsuruhiko Yoshikawa had come up with the idea while studying the American automated machines.

This invention drastically increased the daily production efficiency. It reportedly required only one person for pinion processing, an operation that had previously required 25.

Tsuruhiko Yoshikawa was trained as an expert in the case metal sculpting of pocket watches and had a flair for contriving machine tools for it.

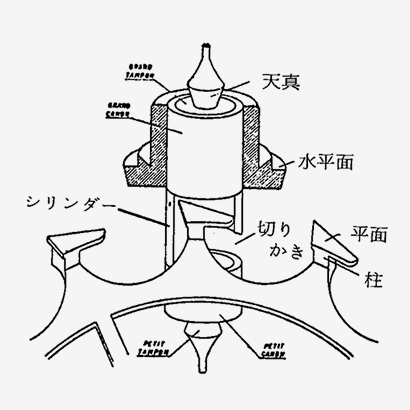

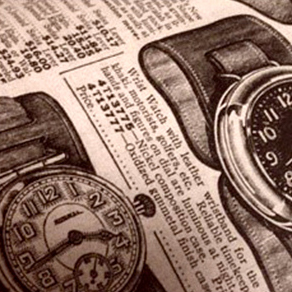

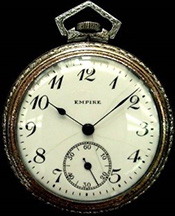

The manufacture of pocket watches started with “Time Keeper” in 1895. The venture was a steep challenge, requiring advanced technology and expensive facilities to produce a complex mechanism and many parts. Unlike wall and table clocks, some of complicated pocket watch components were imported from abroad. Costs were therefore high, and profitability was correspondingly low.

Later, Seikosha was able to manufacture pocket watches of stable quality at reduced costs and sell them at affordable retail prices by completing in-house designs for an automatic lathe and streamlined mechanical designs suitable for mass production. Lower prices led to increased demand, enabling the growth of pocket watch manufacturing as a business

The biggest success as a milestone of the pocket watch is the famous “Empire,” which Seikosha started to manufacture in 1909, at the end of the Meiji period. He continued production from the early Showa period through to the Taisho period.

Vertically Integrated Business and the Launch of Wrist Watch Manufacturing

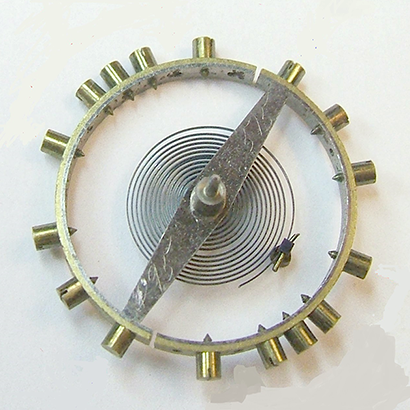

In 1910, Seikosha finally succeeded in becoming Japan’s first in-house manufacturer of the hairspring, the most difficult watch component to fabricate. The Empire thus became the first product made exclusively from Seikosha-processed components.

Seiko’s vertically integrated business model for the efficient manufacturing of all parts in-house with thorough control of quality, delivery dates, and cost, a model still unique today, was completed by as early as 1910.

Confident that the timepiece would eventually become popular among everyday consumers, Kintaro used the well-arranged system he had in place in his factory to launch the development of wristwatches.

Profits from the pocket watch business eluded Kintaro for 15 years. Still, he pressed ahead in his research and development with the long-term strategy of making the pocket watch “thinner and smaller.” Sales and profits from wall and table clocks sustained him.

Japan Pocket Watch Manufacturing Co., Ltd was established in Tokyo as a manufacturer and seller of pocket watches funded by joint capital. Shareholders pushing for capital recovery forced the company to put products on the market before they were perfected. Failing to win customer confidence, the company went bankrupt a few years later.

The abovementioned Osaka Timepiece Manufacturing Co., Ltd. was also forced to dissolve after a gradual decline in its management due to the high cost of pocket watch manufacturing facilities and the overhead incurred by the engagement of more than ten foreign engineers.

As a result, Seikosha is said to have been the only manufacturer still capable of developing and producing pocket watches as of 1910. Sustained by honest management efforts and reliance solely on family capital, Seikosha, a producer of single wrist watch, the Laurel, in 1913, expanded to become the prosperous international presence in the timepiece industry it is today.

Kintaro Hattori, the “King of Timepieces in the East,” contributed more to the development of the Japanese timepiece industry after the Meiji Period than anyone other inventor or industrialist.

References

・Uchida, Hoshimi, Development of the Timepiece Industry. The Seiko Museum

・Hirano, Mitsuo, Company History of Seikosha. Seikosha

・Hirai, Sumio, The story of Timepieces. The Asahi Shimbun