Who is John Harrison?

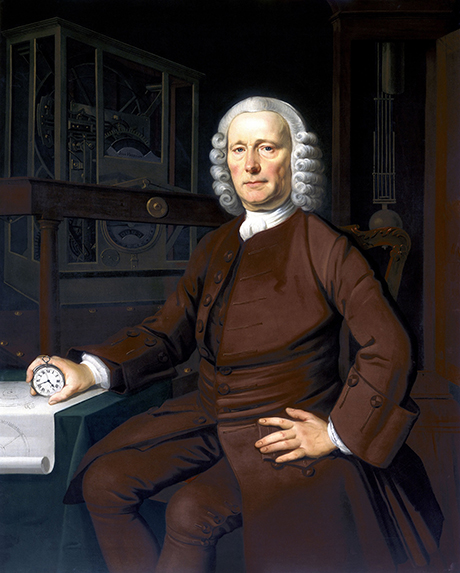

John Harrison was born in Yorkshire, England in 1693. As a youth he learned clock-making technique by himself based on principles of physics and mechanical engineering while helping his father in the family woodworking shop. In his career as a clockmaker he devoted himself to the development of a marine chronometer, a timepiece with the accuracy to determine longitude for safe sailing. His inventions contributed greatly to the accuracy of mechanical clocks.

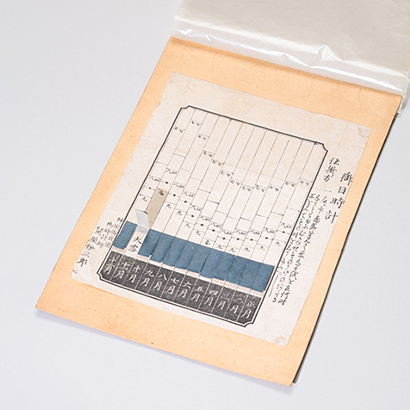

The frequency of maritime accidents and collisions between ships rose sharply in Europe upon the advent of the Age of Discovery in the middle of the 15th century. While navigators could calculate the latitudes of their ships by the height of the sun or Polaris, no method had yet been devised to calculate longitude. In 1707, four warships from the Royal Navy fleet collided with submerged rocks and sunk under the sea, killing 2,000 sailors. In 1714, the Parliament of Great Britain established a panel of Commissioners for the Discovery of the Longitude at Sea and issued the Discovery of Longitude at Sea Act. The first person to find a practical and effective method to determine a ship’s longitude at sea was to receive an award equivalent to a king’s ransom. (*1)

Harrison, who had developed a wooden pendulum clock at the age of 20, set out to win the award by inventing an accurate sea clock. All of the clocks of the time used pendulums, which rendered them useless on a raging sea. Climate and variations in humidity and temperature variations also affected the teeth of the escapement and the mainspring, which hindered clocks from keeping accurate time at sea. (*2)

※*1: The amount awarded under the Act was commensurate with the accuracy of the invention in determining longitude: £10,000 for 1 degree, £15,000 for 2/3 of a degree, and £20,000 for 1/2 of a degree. The testing course for the invention was a six-week voyage from Great Britain to the West Indies in the Caribbean. The award of £20,000 was equal to several million dollars of present-day money.

Spain, Holland, France, Great Britain, and Venice had all rolled out national projects offering reward money for the discovery of a method to determine longitude, starting from around the end of the 16th century.

Eminent astronomers such as Galileo Galilei, Christiaan Huygens, Isaac Newton, and Edmond Halley had also studied methods to accurately determine longitude based on the regularity of movement of celestial bodies in space.

*2: Longitude 1/2 degrees is about 56 Km in distance, as the circumference of the equator is about 40,000 Km (40,000 Km ÷ 360 degrees ÷ 2 ≒ 55.6 Km) and 2 minutes in time, because the distance the earth rotates in a second is about 463 m (40,000 Km ÷ 24 hours ÷60 minutes ÷ 60 seconds ≒463m), (55.6 Km÷0.463 Km≒120 seconds). This was a severe criteria even in present-day terms because it had to be achieved under rolling and pitching conditions over a 6-week route from Great Britain to West Indies weeks with an error of about 2.9 seconds per day.

Invention of the First Marine Chronometer (High-Accuracy Sea Clock)

In 1730 Harrison met Edmond Halley, a head of the Royal Observatory in London, and presented his idea of longitude clocks. Halley referred him to George Graham, a clockmaker then famous for the Graham escapement and cylinder escapement. Graham loaned him money to build his sea clock.

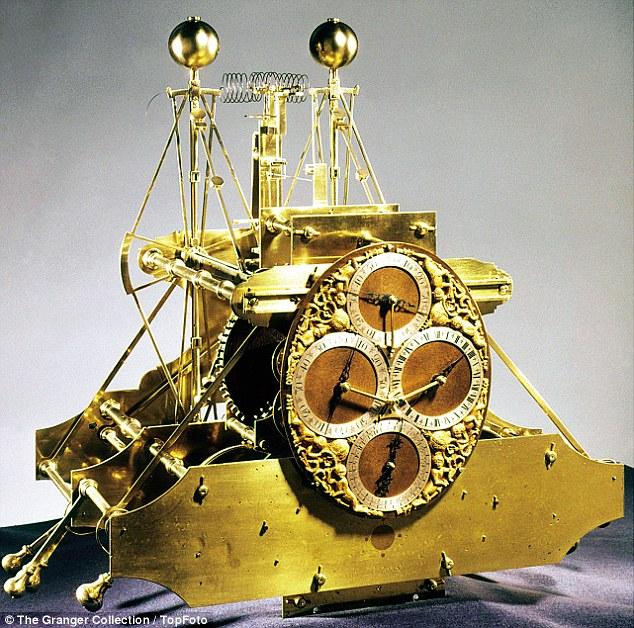

Harrison is reputed to have invented a grasshopper escapement strong in friction and vibration in the 1720s. With great effort, he built a sea clock in 1735 using a mainspring with a wooden gear on a brass structure. He called it the H-1 (Harrison-1). The high accuracy of the H-1 was demonstrated on a ship heading to Lisbon a year later, in 1736. This H-1 was equipped with two dumbbell balances that absorbed the motion of the ship, in addition to the grasshopper escapement.

In 1739 Harrison developed a more compact sea clock with a mechanism to compensate for temperature variations. After the completion of on-land testing in 1741, the H-2 was ready for testing at sea. But by then Britain was at war in the War of Austrian Succession. The experiment was postponed to ensure that the mechanism would not fall into the possession of a hostile country.

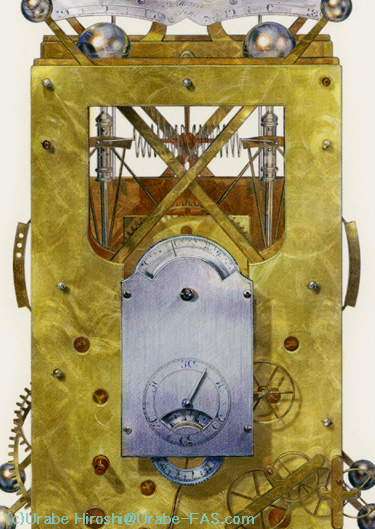

Award for Harrison’s Improved Marine Chronometer

In 1757, after 20 years of great effort, Harrison completed his third sea clock, the H-3, a lighter and more compact machine. In 1761 he developed the H-4, a portable round silver watch with a diameter of only 13 cm. The H-4 remained accurate under temperature variations by resisting the influences of contraction and expansion. Its key components were a new continuous device that worked when the spring was wound and a bi-metal balance with iron and brass. The mechanism, basically a primordial thermostat, was to bring great benefits to engineering in later centuries.

Harrison conducted a round-trip test at sea from Britain to Jamaica through the Caribbean via the Atlantic from 1761 to 1762. The watch lost only 5.1 seconds in 81 days, reaching the level of accuracy required to receive a £20,000 reward.

But just then a rival named Nevil Maskelyne, the head of the Greenwich Observatory and a member of the Commissioners for the Discovery of the Longitude, was vying to receive the same award for his astronomical theory. Maskelyne refused to recognize Harrison’s success. To Harrison’s chagrin, he was granted only a few thousand pounds.

Harrison and his son later developed the H-5, a watch with the same complex internal structure as the H-4 but simpler in appearance, in a bid to acquire the rest of the award. The H-5 achieved excellent results with only 15-second-error over a five-month voyage to the Barbados. At last, in 1773, the 80-year-old Harrison received the rest of the award under the direct patronage of King George III.

The Chronometer that Built the British Empire

The famous British navigator James Cook used a chronometer copied from Harrison’s H-4 for an intrepid three-year voyage over much of the earth, including the Antarctic Circle. The watch was built by Larcum Kendall, who had helped Harrison develop the H-4 earlier. Kendall called his new watch the named K-1 (Kendall-1).

The K-1 told time with only a minute of error over a three year voyage at raging sea under temperature variations from equatorial to antarctic. The accuracy was remarkable.

Cook’s voyage proved that the chronometer designed by Harrison was the most effective for determining longitude. Many other clockmakers were called to make chronometers, which led to the rapid growth of the timepiece industry in Great Britain.

Great Britain, which could then sail the ocean freely, started to build colonies around the world with its gigantic naval power. There is no doubt that Harrison’s chronometer contributed to the British Empire’s immense prosperity as the dominator of the seven seas and the world's factory in the 19th century.

References

Ueno, Masuo The story of timepieces. Hayakawa Shobo

Hirai, Sumio The story of timepieces. The Asahi Shinbun

Deva Sobel Keido heno Chousen (Longitude: The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time). Shoeisha

The story of time and timepieces. Akashi Municipal Planetarium