Who is Hisashige Tanaka?

Hisashige was a prominent inventor born in Kurume who lived and worked from late Edo to the early Meiji period. He was also a major figure in business as the founder of Shibaura Engineering Works, Japan’s first private machine works and the predecessor of one of the nations largest manufacturers of heavy electric machinery (current Toshiba Corporation). He came to be called "Karakuri Giemon," the “Thomas Edison in the East,” for his many elaborate inventions. As a youth he crafted Karakuri mechanical dolls, and later he produced masterwork clocks such as the "Man-nen Jimeisho," the most magnificent Japanese style clock ever made. Outside of his mainstay work as a researcher, developer, and producer of steam engines and cannons, he advanced Japanese technology in other fields by inventing various machines useful for daily life. Hisashige was one of the rare and ingenious mechanical engineers who established the foundations of Japan as a technological superpower.

Determined to Live by "Karakuri" as a Karakuri Entertainer

Hisashige Tanaka was born as the eldest son of a tortoiseshell craftsman. At the age of nine he astonished his family and others by fashioning an "inkstone case with a secret lock" equipped with Karakuri mechanical figures. His eagerness to invent and create was first fueled by reading "Karakuri-zui," an illustrated anthology of mechanical techniques for Japanese clocks and Karakuri dolls and toys published by Hanzo Hosokawa in 1796. Hisashige was all set to inherit the family business as the eldest son, but he asked his father to let his younger brother take over instead. Thus unencumbered, he was free to live with his “Karakuri” and pursue success as an inventor.

Not content to merely copy the original techniques, Hisashige built the first "Karakuri mechanical dolls" to move by forces such as hydraulic pressure, gravity, and air pressure (pumps). His best-known masterpieces were “Yumi-Hiki Doji” (“arrow-shooting boy”), the “Moji-kaki doll” (“letter-writing doll”), and “Doji Sakazuki-dai” (“sake-cup stand in the shape of a little boy”). He traveled to many cities as a Karakuri mechanical doll entertainer, including Osaka, Kyoto and Edo.

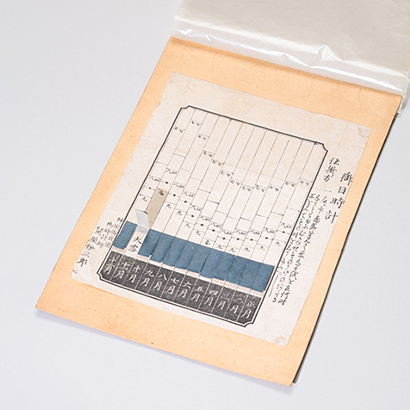

“Shumisengi”-the Masterwork Achieved through the Study of Timepieces and Astronomy

In his middle thirties Hisashige moved to Osaka and produced "Kaichu Shokudai” (“the portable candle stand" ) and "Mujin-to” (“the long-burning lamp"). Later he took an interest in the Western clocks imported into the country from Europe. He began to study mathematics and the Western astronomical almanac.

Harnessing his knowledge and skill as an astronomer and engineer, he produced "Shumisengi" (*1), a Japanese-style clock that overturned the concept of the timepiece upon its completion in 1850. Shumisengi was a masterpiece that perfectly expressed the Buddhist cosmology based on geocentric astronomy. Figurines of the sun and moon revolved around Mt. Shumisen on the faces of the clock. He built the Shumisengi to educate the public about Buddhist cosmology and bolster his religion against the inflow of Copernican theory from the West.

※(*1) One of the remaining Shumisengi is the property of "Ohashi Watch (or Tokei-no-Ohashi)," a watch dealer in Kumamoto City, and remains on display in the permanent exhibition of the Seiko Museum Ginza.

The "Man-nen Jimeisho" Chronometer Showcasing Hisashige's Clock-Making Expertise

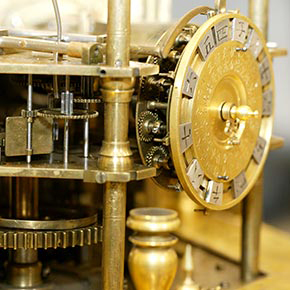

In the following year, 1851, Hisashige completed what might fairly be described as his masterwork, the Man-nen Jimeisho chronometer. He based the design on the advanced astronomical almanac and Western timepiece techniques and crafted the work using his own techniques in metalwork, engraving, inlaid/cloisonné enamel work, and Karakuri. The chronometer is composed of more than 1000 parts, most of which he made by hand. This complicated Karakuri clock can run for a year on a single winding.

Beyond its core functions as a Western clock and Japanese clock, Man-nen Jimeisho sounds an alarm bell and displays the days of the week, the twenty-four divisions of the solar year, the ten stems and twelve signs of the Chinese zodiac (dates in the year of the old calendar), the ages of the moon, and a planetarium (yearly movements of the sun and moon, as viewed from Kyoto). All of the moving dials are interlocked and move in unison by the power of the spring located below.

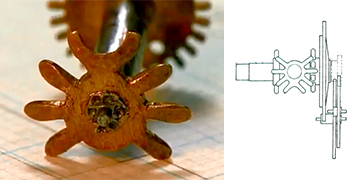

The Japanese clock is equipped with an epoch-making mechanism that supports the seasonal time system, a type of hour that changes in length according to changes in the length of day and night in different seasons, by automatically repositioning and resetting the intervals of the index on the dial plate. This mechanism is enabled by the reciprocating the rotational motion of a wheel with two single gears attached alternately to a unique arrangement of smaller insect-shaped wheels.

Hisashige secured the accuracy of the Western clock component of Man-nen Jimeisho using the escapement mechanism of a Swiss-made pocket watch according to the original design. Based on the movement of the escapement, the mechanism interlocked with the segmented dial panel and hands of the Japanese clock.

The structure clearly expresses Hisashige's commitment "to accept advanced Western technologies and integrate them with Japanese culture in ways useful for society."

This perpetual clock broke down soon after Hisashige's death and has never been restarted in the years since. In 2004 the clock was overhauled for analysis and reassembled in a national project to restore the Man-nen Jimeisho perpetual clock. The researchers assigned to the task discovered complicated mechanisms that Hisashige had developed on his own, as well as clues revealing that Hisashige had made almost all of the parts by hand without machine tools, including the wheels and springs. (*2)

After completing the perpetual clock, Hisashige continued to produce many other unique timepieces with his unique inquiring mind, including his Makura-dokei pillow clock and Taiko-dokei; drum clock (the drum sounded on the hour and the cock crowed the time).

※(*2) This restoration project was carried out by the National Museum of Nature and Science and Toshiba Corporation. Hideo Tsuchiya, a former employee of Seikosha Ltd., was placed in charge of the clock section. As the foremost authority on mechanical timepiece techniques, he produced vast numbers of drawings for a replica to display while the original clock was being restored. The replica appeared at the Expo in Aichi in 2005 and later at the Toshiba Science Museum. The original Man-nen Jimeisho was designated as an Important Cultural Property in 2006 and is regularly exhibited at the National Museum of Nature and Science.

Hisashige in His Last Years

After the arrival of Matthew Perry and his Black Ships in 1853, Hisashige’s interests turned to technologies for national defense to increase Japan’s wealth and military power. He began producing models of a steamship and steam locomotive, the design of a reverberating furnace, and designs for an Armstrong gun.

As the new period of Meiji opened, he developed Japan’s first ice-making machine, as well as a number of bicycles, rickshaws, and rice milling machines. He often said that technologies should be useful for people.

At the age of 73, Hisashige moved to the capital Tokyo at the request of the Government to contribute to communication projects for the modernization of the country. He soon completed the development of a high-quality communication device.

In 1875 Hisashige opened a new workshop with a sign boasting that he could comply with any request for the development of any kind of machine. This was the foundation of the today’s Toshiba, one of the largest company groups in Japan today. Hisashige made prototype telephones, as well as other devices such as the Hoji-ki, an instrument that emitted a time signal across the country.

In 1881, Hisashige Tanaka, the "Thomas Edison in the East," passed away while still immersed in his never-ending pursuit of new inventions. Throughout the unquiet years from the end of Edo to the early Meiji period, he had perpetually explored the forefront inventions of his time and pursued inventions to entertain people. It seems fitting that Japan’s thriving and prosperous watchmaking industry traces all the way back to a Japanese inventor of unique and advanced clocks such as the perpetual clock and Shumisengi in the Edo period.

References:

Hisashige Tanaka - Toshiba's History on the website Toshiba Science Museum

Hirai, Sumio The story of timepieces